The Story

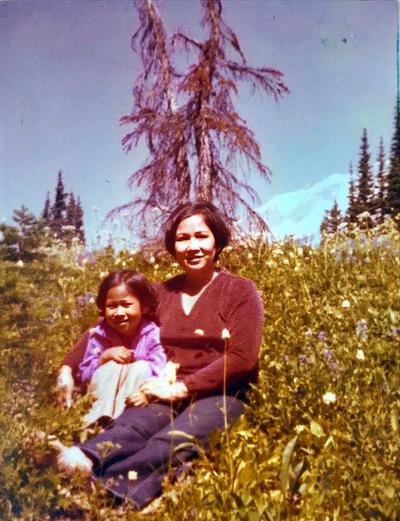

On July 30, 1974, at 11:53 pm, I entered the world with a broken heart. The end of the Vietnam War was nine months away and my mother would soon find herself abandoned by my father, betrayed by people around her, and alone as a single mom raising a dying child. No sooner was I born than a death sentence loomed, for I was given a five-year lease on life, to be revoked at any time without notice. The doctor knew something was wrong with me, but he didn’t know what it was. He sent me home, blue and frail, to enjoy what remaining breaths I had left with my mom. All was not doom and gloom though. Even in times of tribulation, we found joy and laugher. I was a gassy baby and often provided comic relief. When I was uncomfortable, I’d pucker my lips, squeeze one eye shut, and try to cry. Mom used to say I looked funny.

The congenital heart defect I had was called the Atrial Septal Defect, characterized by a hole in the wall between the atria, the two upper chambers of the heart. For the next few years, while South Vietnam fell to her knees and the economy crumbled, and while my mom traded illegally in the black market to put food in our mouths, I, too, was fighting for my life. I was born with boxing gloves on, ready to give the world my one-two punch. It was a fight to breathe and what little food we had, it was a struggle to keep down. Starvation, shortness of breath, fatigue, heart murmurs, infections, and malaria were everyday normalities for me. So on the day we left our home country, it was just an ordinary day. What my five-year-old mind didn’t comprehend was that the real fight was about to begin.

In 1979, my mother discarded her pajama of fear and donned her shirt of tenacity. She wrapped herself in woven fibers of bravery and discreetly left Tra Vinh, with me on her hip and my sixteen-year-old cousin as her shield. The three of us rendezvoused with other refugees and escaped in the thicket of mosquitos to the South China Sea with forty other boat people. Her plans to leave all began with a mooncake that held a secret note with the date, time, and location for the great escape. Many attempts were thwarted, but finally, we were on our way. The rat-tat-tat sounds of AK-47s gave us a sendoff we’d never forget.

Off to the perilous unknown and adrift in the sea for five days and four nights, we quickly ran out of food and water but ran aplenty into Thai pirates, sharks, torrential rain pours, and crashing waves. I never felt so sick in my life. It was bleak. If I wasn’t blue from the poor blood circulation, I was pale from malnutrition or red from the unforgiving sun. Seasickness was the purple cherry on top.

My life was painted in colors of green and red from the time I was born until the day I began elementary school. From the jungles of Vietnam to the jungles of Indonesia, we were surrounded by green uniformed soldiers, green leaves of the forest, and green slithering snakes that fell from the thatched roof of our shack. From the red horizon of a sunrise to the burning flames of our boat, to the red dirt of the region and the soiled blood on our bodies, the only glimmers of hope came in shades of blue. The blue ocean gave us fish to live on and blue crabs to boil. It is no wonder blue, green, and red are my dominant colors today.

My family considered us lucky. We had each other and we were alive. We could still feel pain and hunger. We could still laugh at our dirty, stinky clothes and rotting teeth. We could still ask our God to take the sail and deliver us to the shores of freedom. With nothing to do in a refugee camp but wait, the hours felt like days and days felt like years. My cousin was homesick and yearned to repatriate back to Vietnam to be with his family. He got malaria and almost died at the camp. My mother thought she was going to lose both of us as I collapsed at the camp when my heart gave out. I don’t remember much about our life in the Galang Refugee Camp in Indonesia, but I remember the vulgarity that would come out of my mother’s mouth! My dainty, sweet, soft-spoken, demurring mother often dropped the F-bomb. It didn’t matter if she dropped a banana or if someone died, she say, “Đụ má mày!” While on the island, she swore so much she got lazy with the cursing and shortened it to má mày. Years later, I’d laugh and tease her when she swore because she was too cute trying to be angry and tough. All five feet, zero inches of her would shake like a threatened Chihuahua barking at a timber wolf.

In 1980, on the coldest March day of my life, my family stepped foot onto American soil. We went from the tropics of Indonesia and the Philippines to the wet, muggy coldness of Seattle, Washington, where fish flew at a place called Pike Place Market, ferries shuttled people from island to island, Orca whales sang and visited, and people wore socks with Birkenstock sandals, rain or shine. Then, the battle my little heart had been fighting, eclipsed into blackness. I dropped to my knees and fell down thirteen steps, from the top of our apartment to the bottom of the parking lot.

Seattle Children’s Hospital was where I learned my first two English words: 7-Up, please. The next two words were probably “No Milk.” After six hours in the ER and OR I awoke groggy, hungry, and renewed. I could inhale a lungful of air. It didn’t feel like the monkey on my chest was sitting there anymore. My surgeon and his team opened my chest cavity and repaired the tiny valve that would save my life. Forty years went by before I needed to see my surgeon again… not because the valve failed or that I had another murmur. But before you can understand the impact of the reunion with my surgeon, you have to first understand the impact my mother’s death had on me.

I had a great American childhood but a terrible teenage life. My adult years more than made up for the bad times. I graduated from high school with honors, got my college degree, earned a six-figure salary, and lived the American dream that my mom sacrificed so much to achieve. While I drove recklessly and partied hard, taking 5-hour energy drinks to cram for exams, my mother toiled to make money and free herself from a loveless second marriage. While I flew to amorous destinations, dined at Michelin restaurants, and rubbed elbows with people who had assistants to wipe their snot, my mother sank into depression and never showed me her pain. How alone and helpless she must have felt. She gave me the glory while she truly was the wind beneath my wings.

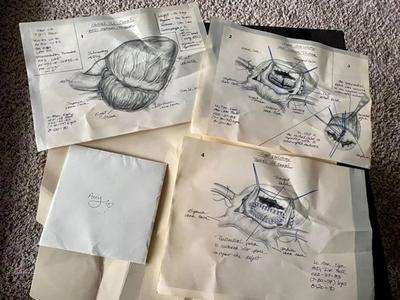

When I got married, bought a house, had more cars than the garage could hold, and a beautiful baby to imprint my dreams and hopes upon, a tumor was growing inside my mother and that tumor would one day take my mother’s life. I lived a privileged and selfish life. I know this now. When my mother was in hospice and there were more than tears that dripped from her body, I tried so hard to force-feed her so her arms and cheeks would be plump again. But God had other plans. He didn’t want her to suffer anymore. The mental and physical trauma she endured, the psychological and physiological hauntings that made her pensive as if she was lost in another time, the sullen twist of her lips when she’d smile cheerfully while her eyes betrayed her feelings…gone. How can a person be there all your life–ease your fears, spank your butt, cook delicious meals, give you unwanted advice—suddenly be gone without a trace? And the only things she had left to give me after 77 years of life on Earth were a few old photographs, hand-drawn pictures from my heart operation, and some jewelry.

For thirty-seven years my mother held on to these pictures of my heart operation, drawn by an unknown medical illustrator. My only clue as to who performed the surgery was the name “Dr. Hall” scribbled on the drawings. It would take another four years after my mom’s passing for me to connect the dots, take the journey to understand my heritage and appreciate my roots, and above all, honor the woman who gave me life. I stepped down from the corporate throne, traded the golden handcuffs for the quill pen, and gave up the security of a steady paycheck. I locked myself away and wrote my mother’s story as well the stories of hundreds of thousands of boat people who left their home country for a chance at freedom no matter where the winds would blow.

Forty-one years after my lifesaving open-heart surgery, I found my surgeon and the medical illustrator who were in that operating room, who offered my mother hope, who delivered a miracle and lit the embers that would one day become this heart warrior’s creed. God works in wondrous ways and sees all the details. He put me in the hands of the only triple-board certified surgeon in the nation at that time who specialized in valve repairs. His angels sent the best medical illustrator to work alongside Dr. Dale Hall to capture history in the making. In 1980, Susan Russell Hall was a young twenty-three-year-old art student about to embark on her career as an artist, and the job she landed happened to be a grueling medical illustrator job that required her to stand for the duration of each surgery and sketch by hand details of the operation. At a time when medical illustration was not even breaking ground as a job, Susan truly was one in a million. She knew as a young child she wanted to be an artist and darn if she isn’t an incredible artist today, successfully selling all her artwork at every gallery showing across the country. To have found Dr. Hall and Susan was a blessing. To have been reunited with them gave all of us a new appreciation for life and the miracles of each moment. To have them in my life is like having a piece of my mom with me again. What a gift for me, a sick little Vietnamese boat refugee who’d one day grow up to become a mother, a wife, an author, and a heart warrior.

“I am a heart warrior. I am a fighter. My strength comes from my faith and is fueled by my perseverance. I am strong. not because of what I can lift, nor what I must endure, but of my sheer will to fight for a better tomorrow. My perseverance is powered by my heart, the muscle that reminds me I am alive. I am a heart warrior. My family is my life. I would die for them as they would die for me. I am not afraid to show pain, insecurities, or doubts, for those emotions strengthen my resolve. They let me know I am human, made in His image. I have courage. I have heart. I will rise and not give up. I am a Heart Warrior and this is my creed.”